Reworking OK Computer -- Pt.III

Free Play

In a way, there is no sense in trying to compose music, or, in my case, humbly trying to notate musical ideas, if the musician does not have the faculty to improvise. I am not absent this faculty altogether, although it has always been a fragile practice. Here, I have played simple waltz-like harmonizations, consisting largely of chord inversions on the downbeat of each measure and employing the same harmony throughout the measure. A run of notes largely forming diminished chords is also employed. It concludes with a hasty retreat to some kind of resolution to the tonic. I will, in future installments, expand on this treatment, working in parallel in the two mediums, mind and paper, and many of ideas I explore freely I may later attempt to formalize in notation.

The Score So Far

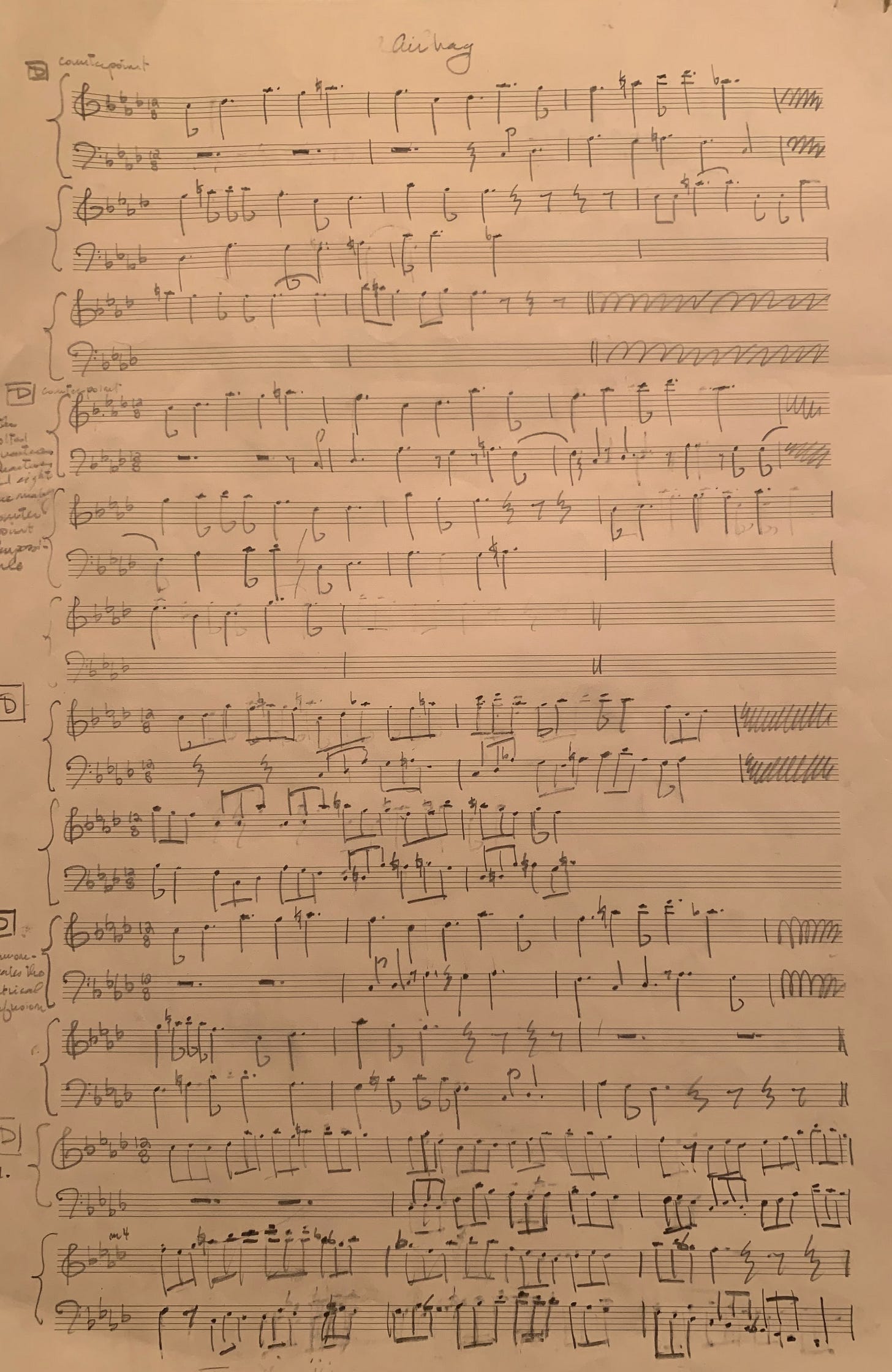

Pg. 1

Pg. 2

Most of the relevant work was done in the bottom portion of the second page. A business interest kept me busier than I should have liked of late, leaving me with less free time to work on this project than I normally enjoy. I was also lackadaisical about documenting some of the more important changes. I will, accordingly, be brief. I will describe, first, my difficulties with producing music via the successive entry of the theme, and then how I resolved this difficulty to my satisfaction.

The Work

One of the reasons to not merely orchestrate the piece is that the specifics have an element of happenstance about them, making it difficult to fully, and usefully, integrate the music into memory. A more intrinsic reworking of the music has the advantage of rigor. Basic consistencies, the satisfying integration of exceptions to these consistencies, and novel articulations of rules, are readily able to be remembered. Reworking my notations so that they adhere more and more to these rules and expectations is therefore desirable, as it will give me practice with the rules of composition, as opposed to merely harmonizing, and, hopefully, leave me with material that I can readily play before an audience. Attempting to be as rigorous as possible will likely also lend itself to any extemporary improvisations on this material. I am, I admit, struggling with these dynamics. The difficulties I am facing would typically cause me to give up my efforts, and indeed I felt that I had not made sufficient progress for the sake of an article, but I did make some progress and realized that the only way to get through these difficulties is to work slowly and progressively.

The classic example of consistent and coherent music, which is therefore highly memorable, is the fugue, although its intricacies often make it difficult to get exactly right. In essence, though, it consists of a musical phrase that is repeated at different intervals, in different augmentations and diminutions, that interlock. It follows a set of rules. I have to admit that I am a ways away from turning Airbag into a fugue, but my attempts have illustrated one concept.

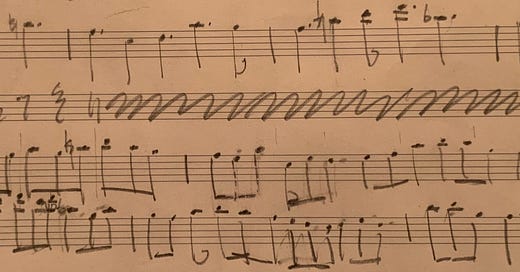

I read, I believe in John Eliot Gardiner’s Bach Music in the Castle of Heaven, that Bach could, upon hearing a theme, immediately assess its suitably for a fugue. Page 2 of my score demonstrates my attempts to straightforwardly notate the successive entry of my theme as it was previously notated. With more experience, I would have recognized immediately that this theme is totally unsuitable for a fugal treatment. As every measure in my notation of the theme consists of an irregular mix of eighth notes, quarter notes, and dotted quarter notes, and as there is no larger pattern to the rhythm of the melody, it is impossible to have the second theme enter without creating metrical confusion, either immediately, or down the line. Important harmonies enter here on off beats. An earlier attempt had ties across measures that muddied the downbeat of the bass stave entirely. It is difficult to subtly change the music in order to produce harmonic clarity when nothing quite lines up, and modulation becomes all the more difficult. Here is notation from page 2 and a recording of that confusion.

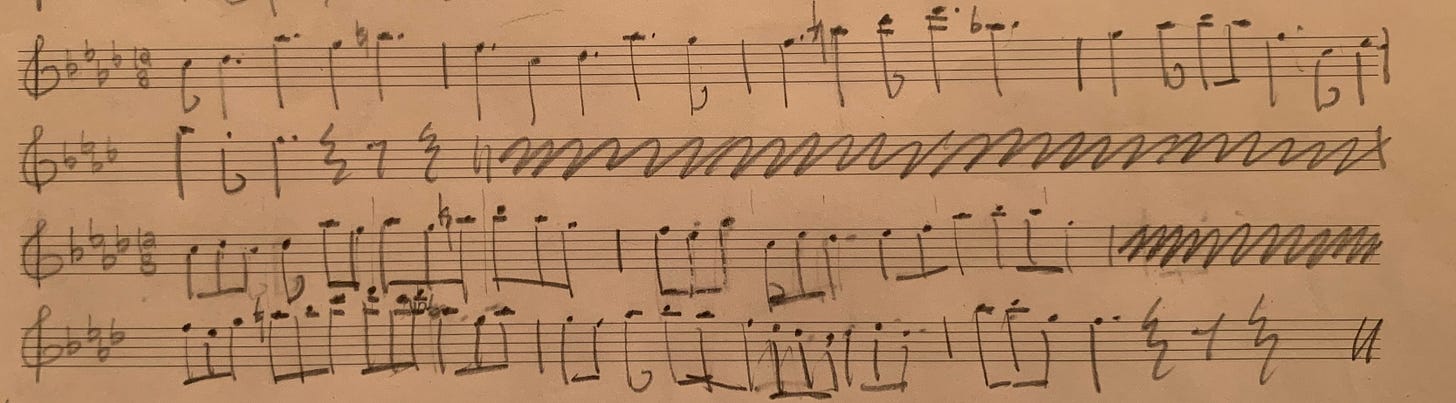

To remedy this, I broke the theme down. Neighbor tones, the notes that are one scale degree removed from any given tone, largely preserve the harmonic importance of the tone to which they are neighbor. Neighbor tones return to that original note. If that neighbor tone instead continues in the same direction that it left from the original note, then it is a passing tone. I broke the theme up into even eighth notes and used passing and neighbor tones to sustain much of the harmonic suggestions of the original theme. This provided me with a much stronger basis for attempting to notate the successive entry of the theme, as now no metrical confusion would be created by an irregular collection of notes of varying length.

Here is a recording of the original theme:

Here it is broken down into even eighth notes:

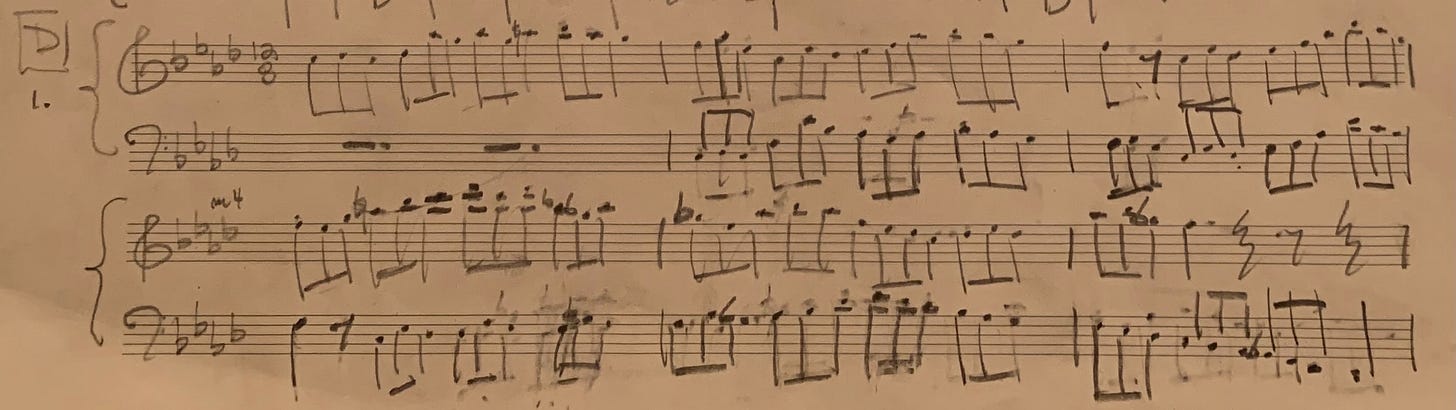

Unless the theme is specifically designed for it, a fugue often has to contend with the ways in which the successive entry of the themes does not quite fit together. I struggled with this in measure 4 of the excerpt below. My solution was to reiterate the opening of the theme and move it up one step each time until I felt I could follow the pattern more normatively. This also required modulating, a topic that I will treat of another time, but it is brought about with the introduction of the g-flat at the end of measure 4. This is why this little excerpt seems to end conclusively on d-flat rather than a-flat. This, for me, does represent progress, but there are no few ways in which it is less than ideal. I will attempt to better conform this start to the rules of counterpoint and voice leading in successive installments.

Here is an uneven recording of the above conducted at a late hour while the neighbors are likely shuffling off to sleep, and would therefore be adverse to continued attempts at it, just to demonstrate and finally get this overdue article out: